Excavating the page with Jazz Money

Jazz Money filming on Biripi Country (2020). Photo: Jennifer Mclean.

Jazz Money is a Wiradjuri poet and filmmaker currently based on sovereign Gadigal land in Sydney, Australia.

Her poetry has won numerous awards, been widely published and reimagined as murals, installation and film. Jazz’s debut poetry collection how to make a basket is forthcoming in 2021 with University of Queensland Press.

This conversation took place in March 2021 on the occasion of Jazz Money’s new Firstdraft Close Contact commission £100000 for No Show at Carriageworks.

Firstdraft: Can you talk about the development of £100000, your site-specific installation for No Show at Carriageworks? What can you tell us about your process – how, when and where does your work germinate?

Jazz Money: £100000 is a response to the Carriageworks site itself, to what lies beneath the foundations of the building. The particular piece of Gadigal land where Carriageworks now stands has a certain element of its history that has been very celebrated, a very recent, harsh, industrial, concrete-clad history… and it is not the story I am particularly interested in responding to.

I started with some very preliminary research and quickly became aware that many historians date the site as beginning (ending) in 1880 when £100000 was paid for the land. The incongruity of such a huge amount of money (more than $16 million today) being paid for land that had been stolen from Gadigal people less than 100 years prior was so grotesque to me and led me down the path of learning about James Chisholm. The sort of fella whose life was so charming that the second line of his bio reads “the two regiments in which he served quelled both Irish rebellions and Indigenous resistance along the Hawkesbury River.” From that point the text part of the piece arrived quickly.

FD: The exhibition design of No Show is quite provisional – unclad walls and open structures bleed into and reveal spaces beyond. Similarly, £100000 excavates sediments that have been obscured over time, revealing the shallow colonial memory – time seems to acquire a spatial dimension. How do you conceive of time and rhythm in your work?

JM: In my practice I’m very interested in memory – First Nations memory, colonial memory, place memory – the stories that get told and the stories that go quiet. £100000 is a very literal response to Carriageworks, I wanted to interrogate the determination to preserve a certain singular ‘Australian’ history and not the deep, sacred, complex and simultaneous. In this colony you only need to scratch at the shiny surface to find violence just beneath. Responding to the earth, the site, with both content and form seemed logical.

Jazz Money, £100000, 2021, vinyl, soil, dimensions variable, installation view, No Show, Carriageworks, Sydney. Commissioned by Firstdraft. Photo: Zan Wimberley. Courtesy the artist.

FD: How do you conceptualise the space or difference between your writing and artmaking? Do you define a boundary between these practices or are they mutually exclusive?

JM: Oh gosh. I’m trying to figure that out!

At the moment I really feel like poetry is my central practice, it is the space I find my thoughts and activism can live most fully and complexly. Being able to challenge the flat page and bring those words into dialogue with 3-dimensional spaces has been a joy and I feel really lucky to have had invitations (thanks Firstdraft!) to consider how poetry can inhabit physical and digital spaces.

“The particular piece of Gadigal land where Carriageworks now stands has a certain element of its history that has been very celebrated, a very recent, harsh, industrial, concrete-clad history… and it is not the story I am particularly interested in responding to. ”

Jazz Money installing £100000, 2021, vinyl, soil, dimensions variable, installation view, No Show, Carriageworks, Sydney. Commissioned by Firstdraft. Photo: Nerida Ross. Courtesy the artist.

FD: Who are some of the poets, writers or artists who have influenced you and/or your work?

JM: The great storytellers of Indigenous and queer communities are the people I hope to honour with my practice. Folk who have fought hard to make sure our voices are heard. I am so lucky to be writing and working in the shadow of brilliant Indigenous thinkers who have created these spaces. In particular, my deepest gratitude goes to Uncle Stan Grant Snr whose preservation of the Wiradjuri language provides a path down which I can walk back to Country and culture.

Jazz Money, £100000, 2021, vinyl, soil, dimensions variable, installation view, No Show, Carriageworks, Sydney. Commissioned by Firstdraft. Photo: Zan Wimberley. Courtesy the artist.

“poetry is my central practice, it is the space I find my thoughts and activism can live most fully and complexly”

FD: Can you tell us a bit more about your debut book how to make a basket?

JM: how to make a basket is a poetry collection that I have been slowly building over the last few years. It won the David Unaipon Award for an unpublished manuscript last year and will be published by University of Queensland Press in September. It makes me feel this wild oscillation of anxiety, joy and humility that folk will be able to read this collection which feels so intimate to my own life experience.

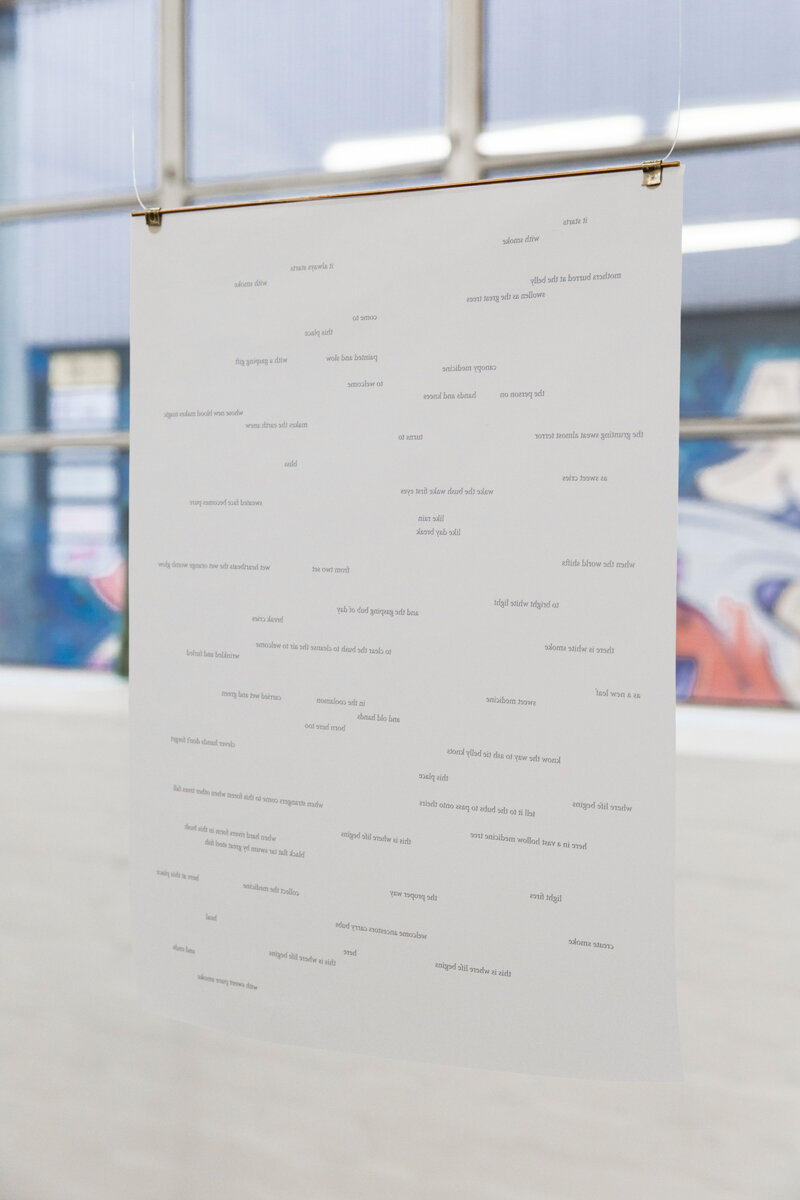

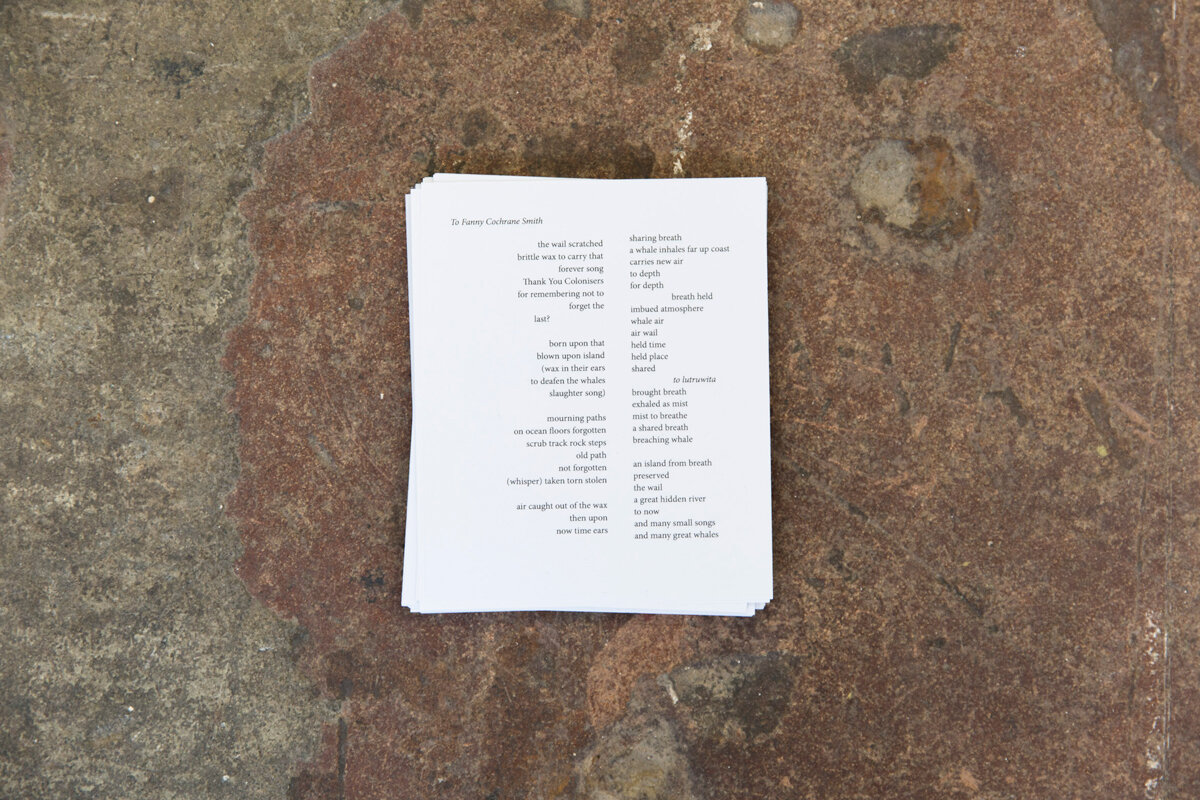

Jazz Money, sweet smoke, 2019, installation view (detail), Relics of Survival, 2019, Bus Projects, Melbourne. Photo: Lucy Foster. Courtesy the artist.

FD: Why did you become an artist/writer?

JM: I gravitated towards the arts seeking solace. I think the arts are the best place to ask questions and have complex conversations. Our society is fucked and writing helps me make sense of the tensions, making art helps me be comfortable in the complexity. These things are an extension of my protest against colonial Australia. I am just always surprised that other people seem to hear and see me through the things I make.

FD: Who or what are you listening to, watching, reading? How do you stay connected – or how do you disconnect – in these times?

JM: I just read Paul Takes The Form Of A Mortal Girl by Andrea Lawlor which is brilliant, dare I say, a seminal piece in the trans literary canon? Set in the early 90s which, as a kid with Gen X parents who grew up in the shadow of that cultural moment, I loved. I’m now reading The Americans, Baby by Frank Moorehouse which is about the Australian obsession with America in 1970s Sydney. It’s so funny and fucked, the sharpest writing.

I’ve found recently I’ve been really gravitating towards queer histories (see also: It’s a Sin, Pose) as a way to feel connected with community that I missed and craved desperately throughout last year. Remembering and honouring our Elders and the fights that have been won for the freedoms I enjoy today is a privilege.

Jazz Money, Bub, Listen Up, 2021, installation view, Here:After, 2021, Fairfield City Museum and Gallery. Courtesy the artist.

“making art helps me be comfortable in the complexity”

Jazz Money. Courtesy the artist.

“Remembering and honouring our Elders and the fights that have been won for the freedoms I enjoy today is a privilege.”

FD: Do you have a favourite or particularly memorable exhibition that you saw at Firstdraft, and why?

JM: The first exhibition I remember seeing at Firstdraft after I moved to Sydney in 2018 was Nadia Hernandez’s “This Is My Army (Este Es Mi Ejército)”. It was so full of joy and pain, love and humour. The other spaces were looking deadly too and I remember being so impressed by how flash and professional everything is in Sydney was lol.

Jazz Money, sweet smoke, 2019, installation view (detail), Relics of Survival, 2019, Bus Projects, Melbourne. Photo: Lucy Foster. Courtesy the artist.

FD: How has the last 12 months been for you? How has your lifestyle and artmaking been affected by 2020?

JM: COVID helped me reassess my priorities. In mid 2020 I proposed to my girlfriend (she said yes yay). In the second half of last year I quit my full-time job as a digital producer at an art gallery to focus on writing, a masters degree, making art and freelance filmmaking. Last month we moved back to Sydney from the Blue Mountains! It’s been a big year, like it has been for everyone, and mostly I have been amazed by how lucky I am to make work that I enjoy and yarn with the most interesting folk.

The Firstdraft Census is Firstdraft’s annual stakeholder survey for 2024. Firstdraft is growing and we want to hear from you during this period of change.