Dance partners in the desert of the Real

Sonya Holowell is a vocalist, composer, writer and educator of Dharawal/Inuit descent. Her work spans many contexts and takes multiple forms, with improvisation as a primary MO. Sonya was co-founder and editor of online arts publication ADSR Zine, 2018–20, and currently runs the project Danger/Dancer with collaborator James Hazel. She is on a new threshold of personal, expository work. More info...

James Hazel is a composer, artist and educator based on the unceded Gadigal land of the Eora Nation. Through the lens of social-class embodiments, James’ work interrogates sound, research, linguistics, scores, writing, performance & video. As someone who was born in Western Sydney, and who grew up in an underclass (social-housing) community, James is interested in what it means to work/live within limited socioeconomic means and how this affects participation in the arts and society in general. James’ work is also focused on the class politics of debt, labour and trauma. In this way, James’ work stems from a mix of his lived and research experience. As an advocate in this area, James has commissioned a number of artists from low-SES backrounds through ADSR Zine (which he co-founded with Elia Bosshard and Sonya Holowell. He is also a co-founder of The Opera Company with Joseph Franklin and Tina Stefanou. More info...

Sonya Holowell and Tim Gray at Bidura Children’s Court. Courtesy the artists.

This conversation took place in October 2021 on the occasion of Sonya’s and James’ Firstdraft Writers Program residency Danger/Dancer. Each produced work while in residence, which can be viewed at the links below.

Interview by Laura Couttie, Co-Director, Firstdraft, 2021–22.

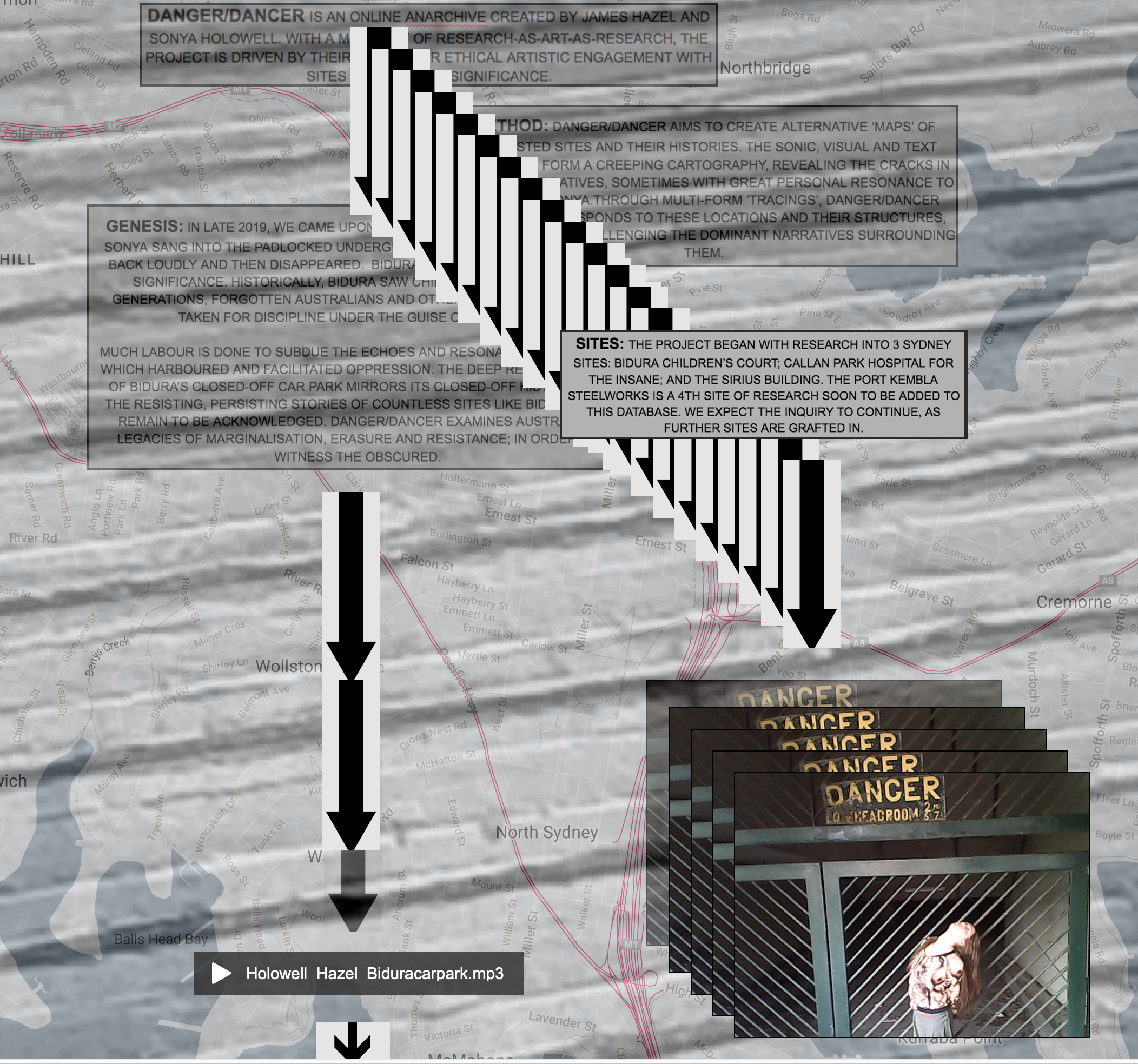

Sonya Holowell and Jamez Hazel, Danger/Dancer website homepage. Courtesy the artists.

Laura Couttie: You are both independent practitioners, but you also share a collaborative practice. Can you tell us about your collaborative project Danger/Dancer and how it formed?

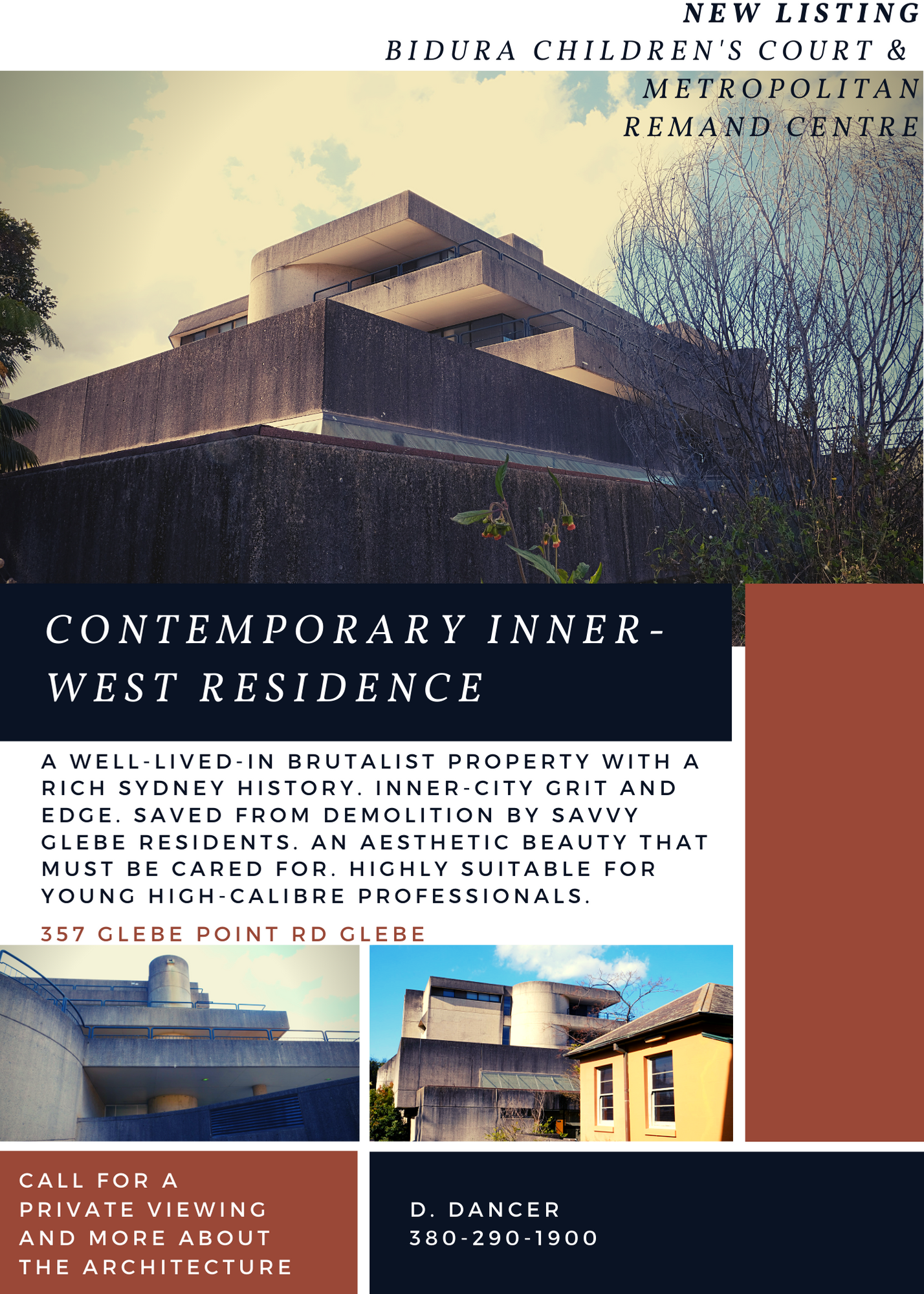

Sonya Holowell: Danger/Dancer originated with the discovery of the old Bidura Children’s Court building in Glebe. It kind of seized us, before we really knew about it or its history and significance. We did a bit of interacting with the building and documented it, and this led to a continuation of research into Bidura, and other Sydney-based sites of significance, particularly to marginalised communities. These often had fraught histories which were under threat of erasure; or maybe histories/truths which never actually had the chance to see the light of day. The sign above the entrance to Bidura’s carpark said ‘Danger’, but it kind of looked like ‘Dancer’ as well. This became a pertinent symbol of the work we both wanted to continue pursuing.

James Hazel: When Sonya first improvised into the depths of the car park, we were both taken aback by the intensity of the reverberation which modulated and disrupted the ‘rational’ continuity of her voice. It was interesting how the project arose out of a chance encounter with the Bidura Children’s Court and Metropolitan Remand Centre – as well as a later reckoning of the ethics of engaging with sound practice in spaces with contested and troubling histories. This was significant for us as we didn’t want to just ‘abstractly’ improvise around a site under threat from being demolished and redeveloped. This gentrifying process (in tandem with a careless sonic activation) posed the risk of (re)muting sites that were deeply implicated in the histories of the Stolen Generations and Forgotten Australians. So, before making any work, we undertook prolonged research into historical sources which would inform much of our sonic engagement with the sites – a form of care-full listening with and through the archives. We also collaborated and consulted with Wiradjuri and Gumbainggir composer and musician Timothy Gray who had first-hand experience of the Metropolitan Remand Centre when he was younger. These two processes generated increased social and sonic ‘fidelity’ around what Bidura was – and how this might come to terms with the ways in which these spaces are culturally mapped, spoken about and socio-historically sounded.

“Danger/Dancer originated with the discovery of the old Bidura Children’s Court building in Glebe. It kind of seized us, before we really knew about it or its history and significance.”

James Hazel, Development Solutions. Courtesy the artist.

Sonya Holowell and Tim Gray at Bidura Children’s Court. Courtesy the artists.

“In many ways the project has evolved to consider not only architectural sites which are affected by gentrification, colonisation, and classism – but also how sound can map the marginalised or subaltern body, archive, or practice.”

Sonya Holowell, process images. Courtesy the artist.

LC: In May 2021, prior to the lockdown, you undertook a month-long residency at Firstdraft. What form did this residency take, and what did this dedicated time and space generate?

SH: The residency provided us a studio at Firstdraft to think and work in. This was handy as James and I live in different cities now, so a place to meet up and do our usual over-caffeinated manic thing was great. It was also really energising to be around such encouraging and open-minded people from the Firstdraft team. James and I had pre-planned our own individual projects to work on, but largely what ended up transpiring were some excellent conversations, and some pondering on potential performances/installations we might like to do at Firstdraft one day. We grew particularly keen on the studio itself as a potential site for this (it has an incredible acoustic and outlook). Our individual pieces that we’ve made have resulted from our conversations in the space, which emboldened me to make my most personally-necessary work.

JH: Our conversations were the most important aspect of the residency for me. The fact that the room we were allocated was completely free from any overt form of visual distraction: it was small, had two chairs and a table – not to mention the severe fluorescent light holding us to account! There was also a small window which gave us a view of the basketball court in the adjacent lot. It was funny because we remarked that the space felt like a police interrogation room. So yeah, we sat opposite from one another and that is sort of what we enacted: we interrogated many of our ideas around what Danger/Dancer is – around who we thought and aspired to be as artists – and how in many ways we felt our practices had sometimes tended towards aligning with institutional vectors in terms of certain thresholds we had observed i.e. what gets funded and what doesn’t; what aesthetics are supported and what aren't etc. It was also heaps interesting that much of our interrogation here initially commenced in a critical register (as many planned projects do) but in the end our conversation was undeniably care-full – like a massaging out of the knots! For me, it is the complex interplay of all of these elements (social, ethical, psychological, and experiential) which characterises the continuum on which Danger/Dancer dances.

LC: You have spoken about expanding the concept of what Danger/Dancer can be. Can you elaborate on these ideas?

SH: We’ve noticed that in past projects, things can begin with a concept that eventually starts to feel too narrow. We’ve both been favouring a less conceptually clean, controlled and ‘consistent’ approach these days, in favour of something more instinctual, multiplicitous, tangled, ‘contradictory’, and un-necessarily polished. Something that even we may struggle to recognise, define, or know how to ‘rate’, but that seems to come forth with a refreshing ease. Actually, these are among the markers we’re following now, that are lighting our paths. So we’ve come to invalidate previous terms, expanding what can ‘fit’ in this project. We want our work to be more inclusive and accessible, to our own selves. One thing we’ve done is expand how we’re defining ‘site’. Because of my personal resonances with some sites we researched (like the old ‘Callan Park Hospital For The Insane’, for example), I’m exploring my self more directly as a site now. Danger/Dancer has become for me a sort of banner or weird ‘institution’. Like shelter and permission, offering a sense of safety and freedom through which I can make certain work. It’s risky, because it’s expository. It’s true, which is dangerous. But it’s also danceful, for the same reasons.

JH: Totally. In many ways the project has evolved to consider not only architectural sites which are affected by gentrification, colonisation, and classism – but also how sound can map the marginalised or subaltern body, archive, or practice; how can we render more transparent mute geographies? These concerns arose out of many conversations we have had about how the material, resonant, and affective qualities of particular forms of art-work can index the socio-historical, bio-political or psycho-social conditions of the bodies of those producing the work – not in terms of mere representation of particular ideas, or Romantic auto-biopic – but in terms of how, say the limitations of a material process, or lack of social or fiscal mobility and capital might give rise to particular agencies, assemblages, intensities, lines of flight – in the very muck and the mire one is working with/through in neoliberal precarity. Our process through Danger/Dancer may also perhaps allude to an acknowledgement of the political possibilities of making along these frail lines.

James Hazel, process image. Courtesy the artist.

“... the space felt like a police interrogation room... that is sort of what we enacted: we interrogated many of our ideas around what Danger/Dancer is – around who we thought and aspired to be as artists”

LC: Thank you for sharing your new works that were started during your residency. What would you like to tell us about these works?

SH: My initial plan for the residency was to work on the text and video aspects of a multimedia project I’d been commissioned to make outside of this residency. The complete work was due for release in September 2021, but has been delayed due to lockdown complications. So as this project was temporarily shelved, I pursued some other writing, which I’ve called Bizarre Rant 1. I see this as very much a continuation of previous Danger/Dancer writing I’ve done. It’s done in the same spirit and with a similar intention. It’s autobiographical.

JH: Similarly to Sonya, my plans changed throughout the process – they always do. I ended up developing a work entitled pre(care)ious score no.1 (hidden injuries), which I later performed in draft version as part of Performance Space’s Live Dreams. The piece is, I guess, an attempt for me to try and compress together aspects of my embodied experience of underclass forms of living and complex trauma, and to seek nodes of resonance or form pre(care)ious coalitions across our increasingly atomised subjectivities, brandings, and identities – towards loving and vulnerable intersectionalities. On another level, the defiant adolescent in me wants to smash all that structural ‘training’ I have learned in becoming a so-called composer – training which is really all about denying the body, obscuring labour, and circumnavigating the socio-politics of sound (why else have bougie concert halls continued to be a thing? haha). Overall, I guess pre(care)ious score plays with imperfections, the paradoxes of class aspirations, humour, sincerity, painful embodiments and messy enunciations, rolling around in the spillover that results from this... a type of co-affective slosh. It was sort of effortless – not trying to contort to particular middle-class modalities of being, reception, speech, and experience. In this way it felt right. I didn’t feel like I had to perform a particular this or that aesthetic. This work is something I can perform in a high art space – or a local poetry night in Gosford. Whatever!

“The residency provided us a studio at Firstdraft to think and work in. This was handy as James and I live in different cities now, so a place to meet up and do our usual over-caffeinated manic thing was great.”

LC: Have you been continuing to work collaboratively during the past few months of lockdown?

SH: We’ve been continuing on our own individual paths, though making work which will inevitably coexist under Danger/Dancer. So in that sense we’ve been collaborating, while following our own respective lines.

JH: I love the idea of thinking of life in terms of lines – the anthropologist Tim Ingold speaks to this a lot. We tend to diverge and then converge in our practices, and that middle-point is Danger/Dancer – a sort of liminality I guess. It’s like, when we require affirmation, we turn to each other and Danger/Dancer for support and that feeds into our own practices and lives. Maybe Danger/Dancer is like a little self-help project too? haha. We also try to avoid regulating, competing with, or chastising each other – which, in many ways, is so typical of the inherited (and dominant) practices of white, upper-middle-class, settler-colonial professional spaces (what a mouthful!).

“Our overlapping ideas and experiences – as well as our differences, divergences and nuances – provide an awesome intermediary for discussion, contestation and working through things together in a supported environment.”

LC: What do you enjoy about working together?

SH: James and I have a lot of common ground in terms of experiences and viewpoints. But we also have a lot of difference which I think helps to broaden and challenge the other. James is one of my favourite people in the world – he’s possibly the funniest person I know. Reflecting my work off of him is always generative and revelatory. I’m super-charged and empowered through our collaboration. I get a lot of inspiration from observing James’ practice, too. The dark humour in his work is second to none. Honestly, that is a very unique balance he strikes. It’s so good, people don’t know if they’re supposed to/allowed to laugh or not. Haha, laughing thinking about it now.

JH: We are both good friends and this friendship has grown through our many collaborations (we founded ADSR Zine in 2018 for instance). Likewise Sonya is one of my favourite people. She has a way of working with materials, text, ideas and voice in such unique and disarming ways that make you really fucking feel something. And our overlapping ideas and experiences – as well as our differences, divergences and nuances – provide an awesome intermediary for discussion, contestation and working through things together in a supported environment. There is something so beautiful about working with friends you trust – and who can have a good laugh at the absurdity of the Grand Art Project in which we are all involved. In the words of Cheryl from Married at First Sight (Season 4): it’s good to have someone who’s got your back (in the desert of the Real)!

LC: What is coming up for Danger/Dancer and also for each of you individually?

SH: I think Danger/Dancer will continue to provide this sort of mythology/framework where we can present our individual and collaborative work. We can keep running parallel, and/or intersect. We’ve been giving a lot of thought to doing a performance installation, and are also re-thinking the website, so it can more suitably convey and support the project as it finds itself now.

Personally, there’s a strong focus on composing and writing, which flourished out of necessity during the lockdowns, and is a place I really want to stay in. Performing is still up in the air at the moment. I do miss making sounds with others, but have really appreciated the opportunity for other outlets to find expression.

JH: I think Danger/Danger will keep interrogating the idea of site, but not just contested architecture site, but the site of subjectivity, of the body, of self – and how this can be conceived of as an (un)mapped domain.

“Bringing visions to bear is very exciting.”

James Hazel, process image Houso dub. Courtesy the artist.

“Danger/Dancer will continue to provide this sort of mythology/framework where we can present our individual and collaborative work. We can keep running parallel, and/or intersect.”

LC: Why did you become artists/writers?

SH: To legitimise my hobbies ;) and for processing of life/memory. Bringing visions to bear is very exciting. Deciding to pursue art as a career was pretty natural, as I’ve had this modelled so much in my family. I’m rewarded when what I’m doing resonates with other people. I think everyone has a desire to be seen/heard/understood, and so that’s a driving force. I do struggle with a sense of not feeling known and understood by others. I’ve had to hide so much, and so much has been hidden from me. So I guess I’m grappling with that and trying to address it in my current work. But I have managed expectations. Meaning that if no one ever gets it (or even likes it), that’s fine. At least I’ve said what I’ve needed to say.

JH: I started writing ‘creatively’ after I stole a copy of William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience from the local high school at 17. I really liked the cover, but I guess I loved that Blake had created an entire, subversive, complex poetic mythology out of pre-existing narratives (such as Catholic theology). So for a kid living in the houso, that has such speculative and imaginative potential. I mean, sculling a goon bag around a clothesline can do the same, but mentioning poetry here makes me sound like I somewhat had it together. So, yeah, I started out writing poems, stories, diagrams, mythologies – tried to make sense of the world in my own obtuse ways. In this capacity, writing is its own social space – something which Fred Moten and Stefano Harney have written about. It was a way to regulate my chaotic and precarious home life, to make sense of it, to process anger, pain and anxiety – and later it became a way to reach out to others and to feel less alone. It is only now that I feel that I am writing better for myself and others because I am not so much concerned with the outcome but that uncanny feeling in the process. In this way I am reminded of some thinking by another high-up (Deleuze) who says writing really works when you are a stranger in your own language. That’s a pretty fucking cool idea I reckon – and something I aspire towards all the time! More generally, I am interested in the complex overlaps with writing in terms of language, sound, music, speech and voice. Writing and speaking to me is an extension of my composition work and vice versa. It’s all a form of utterance, performance, and/or articulation.

“it’s good to have someone who’s got your back (in the desert of the Real)!”

LC: Who or what are you listening to, watching, reading? How do you stay connected – or how do you disconnect – in these times?

SH: I go through genre phases in terms of listening. Right now it’s dancehall. But I cycle through all types of bassy stuff, usually. I’m reading Bible prophecy, and (re)watching Extras, Reno 911 and South Park as a break from depressing crime stuff.

I’ve intentionally disengaged a lot lately. There is a lot of toxicity and stuff I don’t subscribe to out there, so I’ve checked out in a few ways, including getting off social media and moving out of the city. The telephone still goes alright so I haven’t faded into complete oblivion. Trusty email never failed me yet.

JH: I have been watching reality television for years. Love Island is something I enjoy, not only for its high drama and late-stage, capital-realist absurdity, but because of how it reveals vulnerability, intimacy, and unveils particular forms of socio-cultural politics. Maybe I relate, cos I feel as if I am a contestant of the hyper-reality program that is the institutionalised and competitive neo-liberal art world. Haha. But, sure the show is heaps problematic, and ‘produced’ in (super) fucked up ways, but there are deeper and valuable reasons as to why so many people watch programs like this – they are really just looking for catharsis, meaning, drama and consolation. I guess I am interested in why people enjoy programs like this – and the broader parallels to other things. But maybe I am reading too much into it as well haha.

SH: Ok, now that you’ve admitted to that – I am also still faithfully watching the Bold every day. 22 years strong baby.

LC: How has the last 12 months been for you? How has your lifestyle and artmaking been affected by 2021?

SH: The last 12 months have been like the ending of a book- many loose ends tied, dots joined. There’s also separation and loss involved in that. Loss of what you thought you knew/could trust, but gaining the truth. I’m re-situated. But displacement’s in the blood.

Now I’m mostly focusing on the more autobiographical work. Writing is an interesting space to play with the conceal/reveal balance. I can veil and make more cryptic to give me the sense of safety I need to proceed. I can control scope and pace, this way. I know that this veiling means the work will be understood or appreciated on different levels by different people. One person’s sci-fi is another’s real life. It’s just the stuff we hide, finding new ways to come out.

The Firstdraft Census is Firstdraft’s annual stakeholder survey for 2024. Firstdraft is growing and we want to hear from you during this period of change.